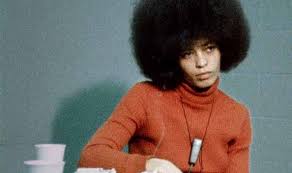

In an interview with Isaac Fitzgerald of Buzzfeed News, Dr. Zinga Fraser discussed the the various moral, personal and political considerations that Shirley Chisholm faced during her first days as a Congresswoman in January 1969.

Dr. Fraser points out that after running an “Unbought and Unbossed” campaign—and as the only Black woman in Congress at the time— Chisholm found herself in a challenging position, both as an independent leader and as an individual confronting the racism and sexism of her day. Accordingly, Dr. Fraser observes, Chisholm could not be “sure about her alliances and the connections to her colleagues.”

With the the nation watching her as the first Black woman in Congress, and a political system that expected freshman legislators to simply follow orders, Fraser adds that it was also an “important time” for Chisholm “to represent her district.”

Among other things, Fraser discussed Chisholm’s legendary fight against what she called “the senility system”—a system that dictated only the most senior and well-connected politicians dictated who sat on Congressional committees. She also discussed the way that Chisholm innovated new ways to effect change for the marginalized in a static, elitist political system, as well the upcoming biopic on the Congresswoman’s life that stars Viola Davis. When asked to give advice on how what the Amazon production (and similar forthcoming projects) can do justice to Chisholm’s legacy, Fraser offered this:

It requires a significant amount of historical background and analysis. We really hope that people stay true to Chisholm’s advocacy, the issues that she spoke about, to infuse that into who she was. And also have a nuanced understanding. She wasn’t just a boring congressional member—she was on fire, she loved dance, she was full of life.

Dr. Fraser’s analysis of Chisholm’s entry into Washington also serves as a reminder of the many challenges faced by the women of the incoming 116th Congress. Many of these leaders, including Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, have acknowledged Chisholm as the inspiration for their own groundbreaking campaigns.